Category: Issue 05

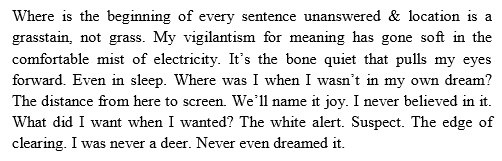

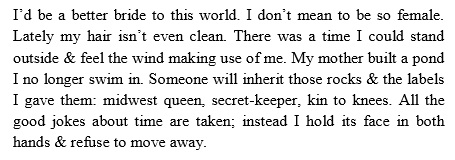

The weekend was suburban & full of efforts to tie down radical hair

*

Holly Amos is the author of the chapbook This Is A Flood (H_NGM_N BKS, 2012). She received an MFA from Columbia College Chicago and is the Editorial Assistant for POETRY Magazine and a co-curator of The Dollhouse Reading Series. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in: Bateau; Forklift, Ohio; H_NGM_N; LEVELER; RHINO and elsewhere.

If my mouth weren’t so full of hammers

*

Holly Amos is the author of the chapbook This Is A Flood (H_NGM_N BKS, 2012). She received an MFA from Columbia College Chicago and is the Editorial Assistant for POETRY Magazine and a co-curator of The Dollhouse Reading Series. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in: Bateau; Forklift, Ohio; H_NGM_N; LEVELER; RHINO and elsewhere.

Vermont

*

(Vermont, dimensions variable, fused and stitched packaging materials, lumber ties, 2011)

Reenie Charrière – Artist website

Artist statement:

“I am invested in everyday moments. My practice is triggered by expeditions along everyday paths, and sidewalks, including public waterways and shorelines.

I investigate by walking, driving and even waiting in traffic, and I am captivated by what accumulates in the environment. Detritus is a menacing punctuation. It comes in all colors and forms. The synthetic bright colors of plastic haunt me as they interrupt and accent the natural topography. I am also drawn to these colors, and their forms as well as the juxtaposition between organic and synthetic matter.

My current work starts with photographing this relationship. Going beyond documentation, I spotlight the situation by fabricating sculptural installations out of discarded packaging materials, particularly plastic, fabric, paper, and cardboard. By sewing, cutting, fusing, reshaping, dangling, and weaving, I transform the material into atmospheric and surprisingly organic-like structures. Many of my installations are integrated with video, projections, and or sound. My choice of materials reflects a collision of clumsiness, and grace and questions how consumerism drives the world.”

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

X-NONE

X-NONE

MicrosoftInternetExplorer4

Vermont, dimensions variable, fused and stitched packaging materials, lumber ties, 2011

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:”Table Normal”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-qformat:yes;

mso-style-parent:””;

mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin:0in;

mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:11.0pt;

font-family:”Calibri”,”sans-serif”;

mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri;

mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin;

mso-fareast-font-family:”Times New Roman”;

mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast;

mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri;

mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin;

mso-bidi-font-family:”Times New Roman”;

mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;}

Terra Nullius

The Romans used the term for land

owned by no one. Easy for conquerors,

and a weapon on its own. Our old

house sat on a little property over

which a creek and road ran parallel,

though the pavement and water were not

ours. The last owner once threw a sack

of kittens into the creek—he couldn’t

afford to feed them or have the mother

spayed. Hearing the story from a neighbor,

I thought of Cicero’s sack in the Tiber,

sewn up as punishment for a felon and stuffed

with a pitbull, monkey, cock, and asp; I thought

of one left a while in the river, never

collected, abandoned to drift down-

stream for days. The bodies distend,

swell, each becoming more

water and, in this, become less sovereign

to itself. A fisherman finds the sack

in the reeds and wades in to heave it

onto shore, buries the man in one

grave and the animals in another. And if he owns

the land into which they were interred,

does he own their lives? Their deaths?

And to whom is it left after the fisherman’s

end? Will cannot be composed, only suffered.

*

Emilia Phillips is the author of Signaletics (University of Akron Press, 2013) and two chapbooks. She has received fellowships from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, U.S. Poets in Mexico, and Vermont Studio Center. Her poetry appears in AGNI, Gulf Coast, Hayden’s Ferry Review, The Kenyon Review, Poetry Magazine, and elsewhere. She serves as the prose editor of 32 Poems, on staff of the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, and as the 2013–2014 Emerging Writer Lecturer at Gettysburg College.

Proximity is the Greatest Motivator of Fear

And love.

————–My worst nightmares

—–are of losing teeth. It’s their

proximity to the brain, why

we say, Let me chew on this awhile

———-or Sink your teeth into

this. When a Life

———-Force helicopter flew over my

father’s suburban home, he made us

duck in the living room.

————–He was on leave from

——–Afghanistan, and I did

———-as he said, not because

I was frightened

but because he was, and nothing I

—–could’ve said could change that. Near

—one another, any two

———————————words begin to

morph, like atoms gifting ions, so that care

—and pressure begin to rhyme, and no and

more, and so whatever you say

—–is is. Next to my father, fear

——-comes close to patience.

*

Emilia Phillips is the author of Signaletics (University of Akron Press, 2013) and two chapbooks. She has received fellowships from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, U.S. Poets in Mexico, and Vermont Studio Center. Her poetry appears in AGNI, Gulf Coast, Hayden’s Ferry Review, The Kenyon Review, Poetry Magazine, and elsewhere. She serves as the prose editor of 32 Poems, on staff of the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, and as the 2013–2014 Emerging Writer Lecturer at Gettysburg College.

There Are 21 Dogs on the To Be Destroyed List

and the journey of a single step disappoints

a thousand miles in all other directions. My dream

of rescue helicopters and sleighs is related to you, dogs

at risk of destruction, but as much to you,

alert citizen. Just think, if I started right now

I could probably make it

to where you are whoever you are

though you might be already gone

in some unforgivable way, where you were

remembering you only as seven dozen balloons,

each cluster the beginning of a city

in a new world I could walk towards forever

and never get to. Can we soften nasty, brutish

and short? Maybe, maybe not, still I feel

like I’m coughing up teeth

and I will never get where we could be going.

There are 21 dogs on a list with a name

that has been rendered by flushing ink

into precise wounds and this softens

not me, but also it is true that we are all

on that list. We were beauties, too,

weren’t we? We thought we were waiting

in cages that moved like train cars

slowing through a town less a town

than the refugee camps we’d been taught to despise.

Maybe we waited in no such cages, maybe

we never didn’t. The journey of one

is a journey of a thousand maybes

cut into by the shrapnel of the voice, the debris

of loving, the heat lightning of a look

crossing a room. I would only have it

many other ways. I want to take a tent

out of my chest full of dancers and acrobats

and a determined, swift girl

who moves from pre-coffin to pre-coffin

to free and lead those to-be-destroyed dogs

like balloons in a stiff wind

to the beach: some will float out over the sea,

others will comb back just ahead of the ebb

until they amble into the city, briefly

well again. The rest remain, trembling

with unmade song, on the shifting lip

where solid ground becomes beauty unthreading

like a slow catastrophe, like clockwork,

like they were born to it.

*

Marc McKee received his MFA from the University of Houston and his PhD at the University of Missouri at Columbia. His work has appeared in various journals, such as Barn Owl Review, Boston Review, Cimarron Review, Conduit, Crazyhorse, diagram, Forklift, Ohio, lit, and Pleiades. His chapbook, What Apocalypse?, won the New Michigan Press/diagram 2008 Chapbook Contest, and his full-length collection Fuse, is out now from Black Lawrence Press. Another full-length book, Bewilderness, is on the way from BLP in 2014.

This Will All End in Tarantulas, I Know It

and it can be hard to know anything else

though we try harder than that all the time

to make beliefs we insist secure us.

You could be standing in a thick, dark night

raked by hovering helicopters.

Their nervous searchlights trace the city blocks

in disappearing squares you think

for a second you are the center of.

You could blink it all away, blink it

all back. “It” could be a phone

conversation that feels like a bear

pawing your prone form

while your insides go berserk

remembering inhaling margarita snowcones

against the giant shoulder

of Texas summer. Such shadows, they

are forever in my mouth until I think

how shadows could be filled with spiders

until I further think how soft they would be

if they just remained motionless and thankful

or turned into kittens. How far does your arm

reach? Isn’t there something a little further

that you want? You could be kneeling beside

the open mouth of a bomb bay, the falling teeth

nearly silent, dumb tumbling, baby acrobats.

I hope you aren’t. What bright tarantulas

result, after all. What gaudy parasols they throw

over each of their shoulders, tethered to you now

with a leash you’ll never let go.

*

Marc McKee received his MFA from the University of Houston and his PhD at the University of Missouri at Columbia. His work has appeared in various journals, such as Barn Owl Review, Boston Review, Cimarron Review, Conduit, Crazyhorse, diagram, Forklift, Ohio, lit, and Pleiades. His chapbook, What Apocalypse?, won the New Michigan Press/diagram 2008 Chapbook Contest, and his full-length collection Fuse, is out now from Black Lawrence Press. Another full-length book, Bewilderness, is on the way from BLP in 2014.

Purchase, Murder, Theft

When the corporation finally comes to bed, he bites her throat, branding her with his mouth, which consoles her. Relationships are work, he informs her.

What is she to him? The rugged individual? The nanny state? She’s insecure, has never felt sure in their relationship–though she likes what he gives her, that’s certain, even if she sometimes wonders if the culture presets her to need what he provides. She offers him chocolates, expensive vacations, tax breaks, each the trace of her affection.

He fattens up, slowly at first, then overnight his bulk consumes the space they once shared. Grown too big, his heart stops.

When they come for him—other corporations, mostly, though some entrepreneurs drop by; parts for sale, cheap—they split him up piecemeal. His mind goes first, in a bidding war. They cart away his arms, his legs, the tire round his middle. She watches, mourns, remembers their first meeting. Him, an upstart in a cheap suit. Her eager, unformed, until he gave her something to want.

Even as scavengers divide the spoils (is this purchase, merger, or theft?) — lymph nodes, brand name, customer base, arterial blood — she wants to be supportive (this is what he would have wanted, isn’t it?), because she loves who she was when she was with him. She collects his leftovers: Fax machine. Tendon slippery with gristle. Rotary phone. Collapsed lung. An office chair missing one wheel. His big toe. Presents for the next corporation come to woo her–larger than life and fiercely desirous—marking

her neck with brittle stolen teeth.

*

Brooke Wonder’s previous work has appeared in Monkeybicycle, Brevity: A Journal of Concise Nonfiction, Clarkesworld, and elsewhere. She is a PhD candidate at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

from Venus Edamame

You can’t be taught by someone you won’t let presume upon you.

/

To understand poetry one must understand the shore. The shore is a line with only one side; that is, what the shore is is not the water.

This alone is not enough to understand poetry. For instance, the poet must ask, “Now that I’ve found the shore, can it be killed?”

In any case, poetry sucks, and all the graduate degrees in the world won’t save us from the flood. Instead of writing poems, let’s give up all hope and suck ourselves dry.

/

This textbook will teach you how to understand poems, participate in intelligent conversations about poetry, and write poems significantly better than you do now. It is not a replacement for an MFA because it doesn’t pay you to teach composition or lead a poetry workshop, but these are both things you can do on your own if you want to.

/

Poetry is not made by humans—everybody knows this—it’s only enabled.

When you read a poem, you’re not trying to “figure out” what the “author” is “trying to say”. You’re reading a poem.

When you write a poem, like really Write a Poem, you’ll know not to take credit for much besides making yourself available for it. Being just how you were at that particular space/time.

/

The Number One skill for a reader of poetry to possess is clearing one’s mind of any knowledge about poetry.

The Number One skill for a writer of poetry to possess is making time for writing poetry.

/

What is a poem?

A poem is something that is not any other thing. Poems often include parts of other things, sometimes other things whole. There are poems that look like essays, for instance, but a poem is not an essay, and an essay, however poetic it might be, is not a poem. Mapping the shore of poetry is the same as mapping the physical shores, the mathematical shores, the shores of history, etc.. Anyways, by the time one has asked, “What is a poem?” one’s already kinda missing the point. And if you really want to know the answer to that question, you will find it impossible to write a poem at all.

/

If you find it impossible to write poems—that is, if all your attempts at poems leave you with a bunch of words that your teachers tell you are excellent poems, and they give you “A”s, if they’re those kind of teachers, ask yourself these questions:

Does what I’m writing mean anything to me at all?

If you mean anything of what you’re writing before you’ve written it, you’re already kinda missing the point.

Am I aspiring to write a poem that has already been written?

As we’ve already discussed, a poem is something that is not any other thing. This includes other poems. Also, don’t try to write poems in a certain “style”. There’s no such thing.

Do I have a reason to write a poem?

If you’re writing a poem to get a good grade, or praise, or laid, that poem won’t be a poem, however much it might work for your purpose. In fact, writing a poem for any reason at all will prevent you from writing a poem.

Does my poem have craft?

What?

Should I change these line breaks?

Probably!

Should I just destroy this and write a new poem?

If there’s any question, the answer is yes.

Have I read everything I’ve written recently out loud?

If you haven’t, you’re too obsessed with books to write a poem.

/

He allowed me to eat much of Donald’s heart before he revealed to me what it was. I realized he wasn’t lying; he’s not smart enough to lie. “Do you feel like a barbarian,” he asked, “knowing that you’ve eaten the flesh of your lover?”

But I didn’t. Almost immediately—I had already begun to feel it, my husband only finally gave it a name—I could feel Donald’s blood mix in with mine, instruct my cells. And I could feel that although I was surely unclean by anyone’s measure, I was no longer measurable as myself.

Naturally, I finished the plate as my husband sat paralyzed across from me.

He had imagined me crying out, flinging the plate, tearing my hair. He had imagined being able to glimpse some sense of guilt in my eyes, and though, he surely imagined, I would certainly kill myself in short order, at least I would know, however I’d try to hide it even from myself, what wrong I had done. Instead, what he saw, glowing there as plain as the sun, was Donald in my eyes and all around me forever.

I set the fork down. I dabbed my napkin on my mouth, letting Donald feel my lips under it with my fingertips. My husband was still caught there, leaning forward, elbows on the table and hands interwoven. He hadn’t even thought. He could never have thought.

/

So say you have three teeth left, and your dog has fifty teeth, and your dog puts his fifty teeth under my pillow. Or say that instead of teeth, it’s fifty whole corpses with a varying number of teeth—how would you go about identifying cancer on your skin? What if the dermatologist is one of the corpses? What if the dentists take the dental records with them, into the flames?

Now, a poem should be enough for most prosecutors to want to see you burn.

If you’re chummy with the executioner, use his trust against him. Let him lead you back to his nest.

Poetry wants to be born, and to find a body first it’s got to eat some people.

/

Let’s say you write a poem about when I write a poem about eating my way out of oblivion. How do you pick a title for your poem?

One method is to pick a word or phrase from the body of the poem, and promote that to title. Often, this will give the poem a subdermal forehead implant. This, obviously, can off-balance the poem. I mean, sometimes it works, and your poem stumbles and trips its way off the tracks just before the train comes. Mostly, though, this method just produces a lot of cancer.

Another method is to voice it up with something long and rhetorical. This method is especially popular on the internet, which is the future, so this is probably an excellent method.

Sometimes, poets will pick titles based not so much on the poems themselves, but on the themes of the manuscript the poems are included in. This will often cause a poet to be perceived as a lot more pretentious than they actually are, and is another reason nobody buys albums anymore, just downloads mixtapes.

It used to be, in the 1990’s especially, you didn’t have to title shit at all ever. Or you could title something “Ampersand” or “Fragment”. Nowadays, you’re much better off titling something “Ampersand pound-sign star star star” or “Frag”. Why? Everyone from the 1990’s is dead, and we’re all figments of the fifty-year-olds who’ll bury us.

/

How do I become a poet?

As soon as you’ve finally written a poem, you’re going to want to turn it into a project, or at least a series of poems. You’ll have all these ideas about how the next poems will grow, who they’ll marry, how they’ll marry, all the things they’ll do and will never do.

Perhaps you’ll keep a page clear in your notebook or pulled up in a background window for possible titles?

And if somehow you get through four or five poems, you’re going to start looking for a publisher.

Many poets will tell you, “Don’t do this! Any of this!” but they can’t stop you. Really, it just depends on what you want to do: if you want to write poems, write poems; if you want to make projects, make projects; if you want to send out poems, send out poems. But none of these things actually make you anything. Writing poems does not make you a poet. Making projects does not make you a poet. Sending out poems for sure does not make you a poet. Getting poems published, too, does not make you a poet. Doing all these things for many years might make you a poet.

*

Donald Dunbar lives in Portland, Oregon, and helps run If Not For Kidnap. His book Eyelid Lick won the 2012 Fence Modern Poets Prize, and his chapbook Slow Motion German Adjectives is out from Mammoth Editions. He teaches at Oregon Culinary Institute.

United Acetates

*

(United Acetates, 32x 48 fused plastic bags, ink, 2012)

Reenie Charrière – Artist website

Artist statement:

“I am invested in everyday moments. My practice is triggered by expeditions along everyday paths, and sidewalks, including public waterways and shorelines.

I investigate by walking, driving and even waiting in traffic, and I am captivated by what accumulates in the environment. Detritus is a menacing punctuation. It comes in all colors and forms. The synthetic bright colors of plastic haunt me as they interrupt and accent the natural topography. I am also drawn to these colors, and their forms as well as the juxtaposition between organic and synthetic matter.

My current work starts with photographing this relationship. Going beyond documentation, I spotlight the situation by fabricating sculptural installations out of discarded packaging materials, particularly plastic, fabric, paper, and cardboard. By sewing, cutting, fusing, reshaping, dangling, and weaving, I transform the material into atmospheric and surprisingly organic-like structures. Many of my installations are integrated with video, projections, and or sound. My choice of materials reflects a collision of clumsiness, and grace and questions how consumerism drives the world.”