Category: Issue 09

Garden In The Iran-Iraq War

In this time, happy branches bow

with young fruit so heavy

limbs must be lopped *** off the trunk. ****** God needs to

******borrow another son. *** Sisters, it’s this,

we say, or your whole garden. And you— *** you will want to hide

your fruit behind the family’s coats in a hall closet—you will want

your sons to stay still, buried

under your long coats, close—their bodies soft. Breathing,

maybe curled up, your boys will wait in a cracked suitcase,

******or a wooden box, *** just for the time

no bomb siren shakes

your trees. No, no one ever really knows. *** Imagine

a night your courtyard’s lit by the fire of burning

*

oranges still clinging to their branches. Remember, this whole

orchard could burn.

*

Aliah Lavonne Tigh has authored a poetry thesis, A Body Fully, and last year, a paper examining the economic backdrop of revolution. She holds poetry and philosophy degrees from the University of Houston and began her MFA at the University of Indiana. Presently, she splits desk time between her second full-length poetry manuscript and research for a smaller historically-themed poetry project.

All The Wild Beasts I Have Been

–After Netanyahu’s statement that Three Israeli Teenagers

“Were Kidnapped and Murdered in Cold Blood by Wild Beasts”

–For Brian

All the wild beasts I have been

Are ripping me apart again

I am a spiritual defector

In the time of

In the time of

I have a million excuses

I have failed

All those years I did not march

All those years I sprung

From some other head

From some other head

As some wild beast

As burning eyes

Of a chamseen

I burned the fields

I burned the wildflowers ******* suddenly

I prayed for forgiveness

Kicked the door in

All the doors in East Jerusalem

Now uncles now aunts now cousins

Calling on my wedding day

Why **** they ask ******* can’t I understand

They will not under any law

Any sun

Any surfacing

Sanction my marriage

They are calling on my wedding day

For those three

Murdered

Teens

For now there are riots on the streets

They live in the middle of things

And have never seen

It did not start with those teens

It has never been a passing thing

The broken glass the sirens

Running ******* running

From rockets and blessing

And once I

Was all of this

I’d come out flailing limb

Explode

Like the eyes of a chamseen

Shelters shelters ducking

No it did not start with this

Kicking down the doors with this

In that BLACKOUT

and RAIDED East Jerusalem

*

*

************Now I am in repose in a Chinese dress

************My finger cast in the Song of Solomon

************The band cast in Hong Kong ****** why

******Why are you calling

On my wedding day

Your voices your reasoning

When I was supine before the streets

Disloyal to the streets

I still chatter in the night while my love sleeps

I am feverish with

In the morning

In the morning

In our new york my love answers me

Knowing you will never speak

To him

He’s just fine my love

Thinks grammar and spelling

Are beside the point

Eguana with an E is just as good

As the real thing

That boy ***** I cry *** that arab boy burned alive

And it didn’t start with him either

With 1500 troops today

and 20000 tomorrow

Gaza on fire Gaza on fire

How will you pray *** I ask *** uncles aunts cousins

When all the beasts

When all the beasts

Call to the parted seas

To the tide rolling in

To the furthest white crest

What then

What of it all ****** drained

Taken of roar and limb you

Call then

************to this other time

*

******************incorrect

*

************************some hours behind

*

******************************with our fruit peels

*

******************hardening on the table

*

************************to this other other time

*

************where he and I he and I

*

************************************each day

*

******************surfacing

*

Born to a Mexican mother and Jewish father, Rosebud Ben-Oni is a CantoMundo Fellow and the author of SOLECISM (Virtual Artists Collective, 2013). She was a Rackham Merit Fellow at the University of Michigan where she earned her MFA in Poetry, and a Horace Goldsmith Scholar at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Her work is forthcoming or appears in POETRY, The American Poetry Review, Arts & Letters, Bayou, Puerto del Sol, among others. In Fall 2014, she will be a visiting writer at the University of Texas at Brownsville’s Writers Live Series. Rosebud is an Editorial Advisor for VIDA: Women in Literary Arts (vidaweb.org). Find out more about her at 7TrainLove.org

Harvesting The Strawberry In The Midwest

35 x 14 inches, watercolor on paper, string, fabric, wheat flour paste, 2012

35 x 14 inches, watercolor on paper, string, fabric, wheat flour paste, 2012

*

Kim Guare is a fiber artist and environmental activist with a passion to share what she has learned about the unethical way our food is produced today. She graduated from the American Academy of Art in Chicago in 2011 with a BFA in watercolor. She is greatly inspired by the organic produce of the farmers market and her time spent working on organic farms.

Artist Statement:

There is a disconnection from the products we buy to eat and where they come from. My artwork demonstrates my concern with our lack of knowledge for the source of the foods we buy and celebrates the beauty of organic whole foods. The subjects often featured in my work are vegetables, fruits, and farm animals. I take my knowledge of food production, and share my ideas with the viewer so one may enjoy the beauty of our food and be challenged by the way our food is being produced.

I would like my work to trigger a desire in the viewer to be more connected to the origin of our food and the natural world.

A Care Package

The box arrived on day three of my residency at the Vermont Studio Center, with my mother’s looping script and Oneida, WI, in the return address. I didn’t expect it, although perhaps I should have, what with my mother’s propensity for gift-giving and house-warming. She had been emailing several times a day once she realized my phone service had evaporated around Fairfax, but I hadn’t opened the emails yet. The year I turned nine my Easter basket had contained six pairs of silk panties rolled up inside the plastic eggs which were usually filled with small change, and which I opened in front of two of the neighborhood boys that year; so, I carried my mother’s package from the dining hall back toward my small studio, deciding to open it in private.

I had already begun to decorate the room allotted as studio space, filling the bookshelves, organizing supplies into the drawers of the desk, and pinning up photos of my family and travels. The surface of the desk was still bare, except for my laptop and the package. Once opened, I arranged its contents in a careful composition for a good Instagram.

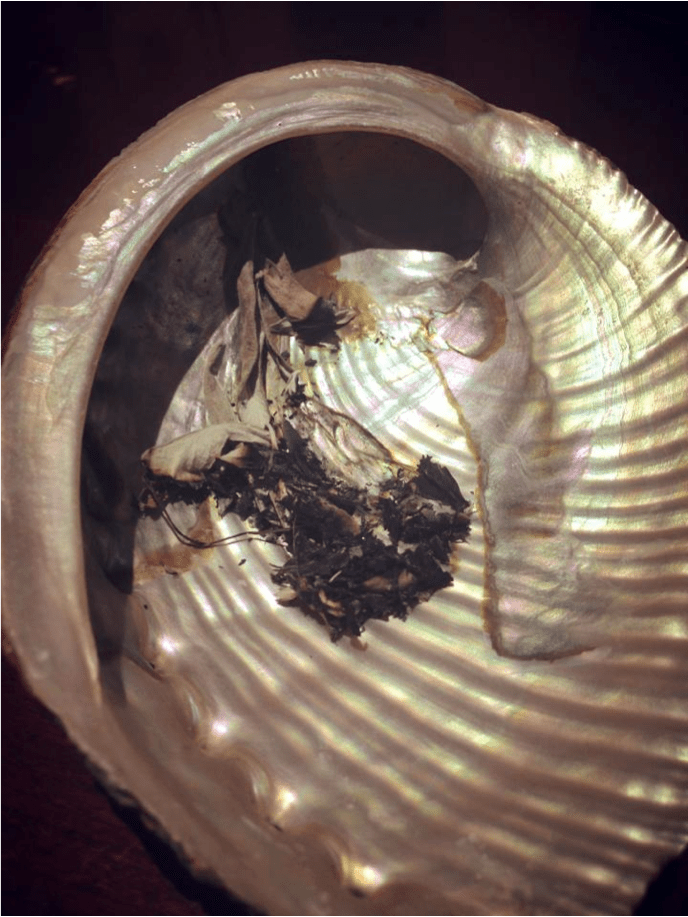

A new cowboy hat, with knotted “turquoise” accents. A selection of jewelry—treasure necklaces and inlaid pieces from the southern tribes, and beaded square droplet earrings with loud pink butterfly motifs. A squashy foam buffalo, branded Oneida—casino-swag. An issue of Cowboys & Indians magazine (I could not tell if this was meant to be ironic). A set of handmade books printed at the Oneida print shop, and, a copy of my favorite Oneida folklore myth. On the inside cover, my Oneida name, written out by our Namegiver, Maria, in shaking script. But it is the abalone shell and the bag of sage that make me feel the most at home.

With these last items, I can smudge my studio. I breathe more deeply. I feel more rooted. The smudging ceremony is still somewhat new to me. We place the sage in an abalone shell and light it, blowing softly ‘til the flames catch and the smoke twists upward, and we waft the smoke over the area or person to be smudged so the bad spirits will be chased out. It is not a ceremony my family practiced much before we moved back to our reservation. But it has since become foundational, a comfort in the same manner as the crosses above my mother’s every doorway or the short, low white fence around a yard, effective because of faith and familiarity. We smudge a room to clear it of negative energies before habitation, we smudge a person to free them of negative thoughts, and smudging my studio would ensure any residual energies were cleared away and that my own artistic endeavors would begin on the right foot. That is what we believe. It touches me that my mother thought to include these items, as some acknowledgment, or perhaps manifestation, of the presence and importance of my culture in everyday life. Not just the myths and storybooks, the branded symbols, but the items needed to enact my culture, jewelry to display proudly the creativity of my people, and the abalone and sage for ritual. With this care package, my mother hasn’t just reminded me who I am, nor has she limited herself to “silly, fun things,” as she claims. My mother is at once acknowledging my identity and giving me tools to hang onto it. Within the package are keys to living Oneida.

One of the downsides to growing up away from our reservation is my lack of integration, and the markers of culture I missed out on as a child. I never attended Pow Wows in a jingle dress, so my mother was never patiently sewing on its last bells before a smoke dance competition. I did not grow up tasting frybread (but I will pull the car over immediately if I see it advertised on a hand-painted sign outside Gallup). I didn’t go to Turtle School or the Oneida Community College, and I have never met many Oneidas my age. My mother didn’t teach me my language, nor could she. So much of our culture is passed down from our families and particularly our mothers, and so much of who I am has been given to me by mine—yet I find gaps in my understanding, holes in my experiences, and spaces that are filled with other memories, the states and counties I lived in, the Girl Scout troops and after school latchkeys of each new city.

My upbringing was different. I am still learning the inside jokes. “Indian” still feels funny in my mouth, even as I hear my mother say it again and again, even as I see us all asserting our own identities, reminding ourselves as much as each other, that this is what we are, this is what little we have been given, this is what little we have been given and will hang onto with ferocity.

Our culture is a gift. A birthright, yes—transmitted by the hands of our mothers as they tape up cardboard boxes and write out our latest zip codes. I smudge my studio, and offer to smudge the studios of my fellows at the residency, who all accept, who all say how peaceful they feel, as I do, when the smoke curls up into the corners of the room.

I still hear my mother telling me, “You are Oneida. You are Oneida,” as I leave for school in the mornings, as I come home telling her about George Washington and the Indians at Valley Forge. “You are Oneida,” she says, when I complain that my skin is too dark, never knowing I would think back to that skin so longingly, say wistfully, when I was younger… “You are Oneida,” my mother says, when it starts—how much? You’re not really Indian—she says “No one can take it from you.”

And when I ask her, even us? Even the other Oneida? Even the Bureau of Indian Affairs? She says “No one, honey bunny, not even you.”

*

Kenzie Allen is a Zell Fellow at the University of Michigan Helen Zell Writers’ Program, and a descendant of the Oneida Tribe of Indians of Wisconsin. Her poetry can be found (or is forthcoming) in Sonora Review, The Iowa Review, WordRiot, Apogee, Day One, and Drunken Boat, and she is the managing editor of the Anthropoid collective.

Shades Of Eggs

8.75 x 5.25 inches, thread, metal, 2013

8.75 x 5.25 inches, thread, metal, 2013

*

Kim Guare is a fiber artist and environmental activist with a passion to share what she has learned about the unethical way our food is produced today. She graduated from the American Academy of Art in Chicago in 2011 with a BFA in watercolor. She is greatly inspired by the organic produce of the farmers market and her time spent working on organic farms.

Artist Statement:

There is a disconnection from the products we buy to eat and where they come from. My artwork demonstrates my concern with our lack of knowledge for the source of the foods we buy and celebrates the beauty of organic whole foods. The subjects often featured in my work are vegetables, fruits, and farm animals. I take my knowledge of food production, and share my ideas with the viewer so one may enjoy the beauty of our food and be challenged by the way our food is being produced.

I would like my work to trigger a desire in the viewer to be more connected to the origin of our food and the natural world.