Category: Uncategorized

THE GOD OF THE WHITE DOG by Elizabeth Moylan

They crowd us from the train and into the chill of the night air. It is again November. There is no

light but the light of the moon. She is full and shines through the tangled limbs of barren trees.

Move, the officer of the peace grunts, and disoriented you stumble to your knees. Move, he says

again, the sound sharper and shriller this time, and you try to get out of his way, but you fall to

all fours. Your own shadow prevents you from seeing your hands in front of you, inches from the

edge of the platform. The moon has betrayed you by offering your back to his eyes. He kicks you

hard in the ribs. You wince as pain crackles electric through you. You hear the bone as it snaps,

shards of rib pierce the surrounding tissue. You curse the bitch of the moon. You are weak, weak,

weak, so weak, you’re not even that old, and yet you are so weak, he whispers into your ear, his

body heat sudden upon you. You are caught, he has you in the posture of an eager, submissive

lover. You fight a wave of nausea. You feel his erection as it strains the coarse fabric of his

uniform. You eat the image you cannot see. You remember the First War, how the officers were

still human then. The boys they sent out into the desert returned, changed. The White Dog

disfigured their souls out there, in the expanses of white sand beneath whiter sky. You remember

hearing that they went mad as they could no longer distinguish the horizon line and to their eyes

all was as blankness and it was then that the White Dog appeared and became their master. You

remember hearing the White Dog made them partake of the flesh of their fellows. You remember

hearing they died and were not dead. The puncture in your side pulses with the explosive

brightness of a dying star. You leak light you cannot see. In ending, everything shimmers. How

can you be this weak, he says, his lips wet against your ear, his breath hot and sour. He wraps his

right hand around your neck, his hand is so large that it encircles your throat completely, easily.

He is such a large man. I could just squeeze and throw you, limp, onto the tracks, his voice

resounds as though from deep within your body. The air in your throat is vibrant with

constriction. Indeed, the autonomic functions of the body have a terrifying insistence. And just as

sudden as he was upon you, his hand is gone and you can no longer sense his presence, his

weight and his heat have vanished. You still can’t see your hands in front of you. Minutes pass

though they might be ages. You finally think to lower onto your forearms and roll onto your

back, safely away from the edge of the platform. You look up into the face of the moon now

above the trees. She bathes you gentle in her light. You remember the piano key in your left

hand. The last remaining piece of the only thing your mother ever loved.

Bio: Elizabeth Moylan is an artist, writer, and educator based in Brooklyn. She holds a BA in Gender Studies from the University of Chicago, where she also studied Russian Language and Literature, and an MFA in Painting and Drawing from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where she was an instructor of painting, print media, and fiber and material studies. She has also taught through the Brooklyn Public Library and been a guest lecturer at the Rhode Island School of Design. She has been a featured reader at Verses in Vinyl at All Blues and will be a featured reader at the Out of the Box reading series at the Bowery Poetry Club on March 11th.

Home is where she is: Notes on Nikki Giovanni’s Life and Work by Nicole Alexander

it’s not the crutches we decry / it’s the need to move forward / though we haven’t the

strength. This opening line from “Crutches” often plays in my head in a grainy voice with a

syrupy sweet pitch. There was a time when this voice would play in the speakers of my 2004

Lexus as I drove from another bratty two year old’s greyly decorated home. These lines were my

play, my comfort, and although the speakers of my 2004 Lexus were my favorite place to access

them, they squatted themselves into my being the very first time I heard them. Wherever I am,

engaging with Nikki Giovanni’s work makes me feel at home.

When I was introduced to Nikki Giovanni’s album, Cotton Candy On A Rainy Day, I was

in a lover’s room. Although it wasn’t my own, her voice came on and solidified an intimate

familiarity I felt in the space. A prior knowledge of the spirit rather than the mind emerged as I

asked about Nikki Giovanni’s life and writing. There was twinkling in my chest, a wash of an

oceanic breeze tingling over my body. Because of this auditory introduction to Nikki Giovanni’s

work, I am mostly drawn to her voice as well as her words. When reading poems, I often feel

like someone is standing over my shoulder and whispering the words onto the page in front of

me, particularly when I can relate to what is being drawn up through the crosses and curves.

Miss Nikki is who I have this feeling most viscerally with.

After hearing them over and over, mostly in my room and in my car, I read “Crutches”

and other poems from Cotton Candy On A Rainy Day aloud to myself. “Crutches” speaks to the

emotional bandwidth we all have as humans, the pain that comes with feeling, and the even

greater pain that comes with asking for help outside of ourselves to handle the rumblings of the

heart. Any person intent on expressing and experiencing their deep feeling will feel seen by

Giovanni’s words:

i really want to say something about all of us

am i shouting i want you to hear me

emotional falls always are

the worst

and there are no crutches

to swing back on

Here she takes the time to scream loudly about something that is usually experienced in

quiet, in solitude. She takes the time to place herself amongst “all of us,” declaring that although

our pains may be unique, this intensity of feeling is universal. It is within her own comfort in

naming the depths of her soul and honoring its rough edges that I am able to feel at home. I am

able to feel comfort in feeling.

As a child, I was resistant to feeling emotions like sadness, anxiety, disappointment, rage.

As I’ve grown older, I’ve been intentional about letting myself feel these feelings, allowing themto course through my blood with gratitude for the heat. Hearing “Crutches” gives the little girl in

me a warm embrace, telling her something she could never quite understand: It is okay to feel.

Through this poem and many others, Nikki Giovanni allows me to regain a closeness with

myself through her own interiority that serves as a mirror for what we must all face. Her comfort

in herself became a place for me to lay a pallet down.

Love, in its ever evolving expansiveness, is a central theme in my work. In diving deeper

into Miss Giovanni, I was drawn to poems where she overtly expressed her sexuality, eroticism,

and desire, most notably in her collection of Love Poems. It was through poems like “That Day”

where she declares: “we can do it on the floor / we can do it on the stair / we can do it on the

couch / we can do it in the air” and “Seduction,” where she imagines a scene of her using the

power of the erotic to seduce a fellow revolutionary, that I was able to see more possibilities

within myself and my own writing. Before Nikki Giovanni’s work, I hadn’t engaged with erotic

poems. It was particularly surprising for me to come across erotic poetry by a Black woman

writer. With dually sexist and racist figures like Sarah Baartman constantly swirling around my

psyche, it took time for me to come to a place of feeling comfort in my sexuality rather than

shame. Nikki Giovanni’s firmness in being forthcoming about her sexuality, amidst these

negative stereotypes surrounding us, was a sprinkle of encouragement as I went on my own

journey to embrace my eroticism rather than hide it. To do so in an artistic medium such as

poetry—a practice that is often seen as highbrow—is even more of a statement. She laid a

foundation for Black women like me to be in touch with their sexual selves and not allow that

embrace to take away from their intellect and active dreams towards the revolution.

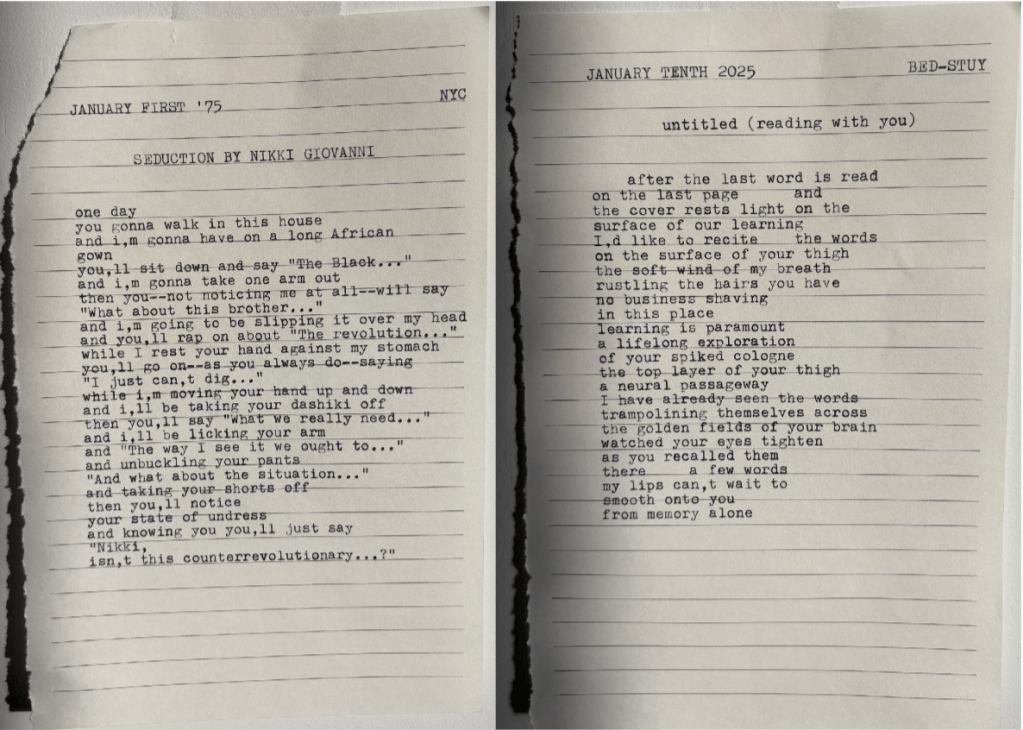

Seduction by Nikki Giovanni and untitled (reading with you) by me.

Her consciousness is always in my subconscious.

I have a great appreciation for the wandering essence of Nikki Giovanni’s work. Many of

her poems feel like a journey. Take “Fascination” for example, where she starts off saying:

finding myself still fascinated

by the falls and rapids

i nonetheless prefer the streams

contained within the bountiful brown shorelines

Giovanni shows us her awe at the natural world, the simple beauties that capture her eye.

Within two stanzas, she turns her attention to an unnamed person saying:

my head is always down

for i no longer look for you

The awe of the world around her takes her mind to the awe of a special person in her life,

an unexpected yet natural curve in the journey of the poem. At the start, one would assume that

the poem will continue in the space of nature, but the wires of Giovanni’s mind always want to

take us on a wild ride. She continues to speak to her lover while weaving in the atmospheric

condition:

i wade from the quiet

of your presence into the turbulence

of your emotions

i have now understood a calm day

does not preclude a stormy evening

We are able to see the connections sparking in her mind and go on the ride with her. She

gives us room to expand the bounds of what can transpire in a poetic journey. At the end,

Giovanni takes us right where we began saying:

if you were a pure bolt

of fire cutting the skies

i’d touch you risking my life

not because i’m brave or strong

but because i’m fascinated

by what the outcome will be

I love the direct usage of the word “fascinated” in both the beginning and ending of the

poem. The middle of the poem zigzags in a way, taking us from one idea and quickly veering

into the next, but that word “fascinated” grounds us back into the awe and wonder that we were

introduced to from the start. Where the words in the middle of Giovanni’s poems go is usually a

mystery to me, but by the end I can feel her palm covering the back of my hand knowing that we

have walked along an unforeseen path and transformed together.

The journey she takes us on in a poem almost acts as a mirror for the journey of her life,

with many unexpected twists and turns that are still logical within her grand plan. Miss Nikki

started her career showing us her anger, her truth, and her allegiance to her people. While that

energy certainly didn’t leave her bones, she allowed it to take new shapes. She showed us her

rage, but she also showed us her love. Miss Nikki’s work took on many forms—poetry, essays,

children’s books, albums—and she lent her knowledge to students directly by becoming an

educator. It’s as if she had a few different dialects to choose from when asserting her aliveness

and in turn, asserting ours.

In the fall of 2023, I found myself meandering through stacks of poetry at the library:

another home for me. I scanned the rows for “G” and was delighted to find a first edition copy of Nikki Giovanni’s debut, Black Feeling Black Talk Black Judgement, asking to be placed in my

hands.

The squealing was as internal as I could make it, my twenty-four year old self suddenly

turning ten, my breath a wind we hear as we take in the still beauty of an oak from a bench. I

hurried to check it out, the corners of my mouth gleaming, my eyes a lake of admiration. Upon

cracking the cover open, I was met with the evidence of others’ exploration of Miss Nikki, dating

back to the eighties.

In her words, I was most struck by her audacity. At twenty-five—this time capsule of her

spirit at the time mirroring my present reality—she did not leave a word unsaid, particularly in

“The True Import of Present Dialogue, Black vs. Negro”:

can you kill?

a nigger can die

we ain’t got to prove we can die

we got to prove we can kill

Through her rage towards systems of oppression, she showed the love she had for her

community. There lays a pillowsoft beckoning in her words, an open invitation to feel at home in

our rightful anger. She knew from age twenty-five that these things had to be let out, written

down, and memorialized. This philosophy, which is a central characteristic in her work, is an

integral lesson for everyone in the community, especially revolutionary Black folks.

The evolution that comes between my two favorite works from Nikki Giovanni—Black

Feeling Black Talk Black Judgement and Cotton Candy on A Rainy Day—is stark. Her first work

was extremely militant, looking at the oppressive forces at work outside of her and interrogating

its effects. Cotton Candy On A Rainy Day turns her energy inward, interrogating how her own

actions/thoughts/beliefs affect her. The militancy is still there almost a decade later, but with a

new face. She is intent on confronting herself. Who are militants and activists but deep feeling

people unafraid to let their emotions show? The revolution requires changes outside of us, but it

also requires a revolutionizing of the self through knowledge and introspection. It was as if she

came to know, as she matured, that the revolution had to start with herself, deep feeling and the

expression of it the way to get there. She showed us herself so we could have the courage to look

at ourselves. She showed us herself so we could become partners in struggle. For Miss Nikki, it

was clear that she was always thinking about us as a people, and her “I” within her introspection

was one of community, one of oneness. It was important that people felt comfortable being their

Black selves alongside other Black people. This cultivation of community serves as another

manifestation of home.

As we mourn the recent loss of this poetic giant, lover, revolutionary, and teacher, I am

content with the knowledge that she will continue to be a beacon for the people. Nikki Giovanni

will continue to speak to us through whispers real and imagined. My everlasting connection to

her work will give way for me to feel a comfort in her, through her, and inch closer to an

understanding and mastery of the self. She did the hard work of finding home within the bonesshe lived in so we could do the same. I know that wherever her work is, wherever I can access

her, I am at home.

Bio: Nicole Alexander is a poetess and educator currently based in NYC. She graduated from Syracuse University in 2020, earning a BA in English and textual studies with a concentration in creative writing. Her recently released, Why I Love Dreaming, is her debut collection of poems.

Poem #3 by Josh Ilano

Poem #3:

Espousing bitching indignities in the

Crosshairs of Bayard and Baxter

Weaseling into the lower ranks

Of the General Men, of the

General Phalanxes—

A horseshoe as admission.

The fallen Babylon being

Remnants of those gentrified watering holes

Still home to skeletoned

Carhartt but Alien to such pale

Faces.

Erupting cocks and breasts and all that

Has been cut, spliced, or spatchcocked between,

Because eye bags are back!

And so are unemployment benefits

And so are the slums

And so is XXXXX XX XXXX XXXXXXX

And so Is that lippy vocal fry

And so is Nicorette

And so is incest

And so is age play

And so is pregnancy

And so is al that provokes the provocative

To deliberate upon these TV-minded Philistines.

Whisper in my ear and

Put your tongue back in your fucking throat.

Write me something in script,

Rhyme to revive Mr. Whitman.

Give back the Grandmother her cane.

Bio: Josh Ilano is a New York-Based Writer and Journalist currently pursuing their undergraduate at Pace University. Josh’s poetry and creative nonfiction has been featured in the literary magazine Aphros. They were previously the Arts and Culture editor of the collegiate newspaper The Pace Press, and currently holds a position on their executive board. Independently they publish on their Substack “Dillinger,” and asides from writing, they freelance with Columbia University’s Directing MFA program. Josh aspires to buy their motherproperty in Nebraska one day.

Two Poems by Insiya Taj

Bargaining

Forgive this island. Its spoiled midnight.

Its damp moon. Its black surf, an altar

seducing you. This is your life.

Your youth, a goldfish in a glass bowl.

Record the ocean’s rhythmic pulse for your grandmother.

Go. Gather the stillness in your fists.

Your hungry limbs. Cage your pulse. Slip into the Pacific.

Allow the sharp tooth of the sea

to graze your bare legs. Let Fatima’s gold hand gasp

against your neck. Ignore her.

These days, she barely listens to you.

These days, she’s less pendant,

more noose. Still, the surf wrinkles

under that tart, black sky.

Fashion yourself into a sponge

and float like a plank.

There is honor in granting a crisis permission

to swallow you whole.

To spit you back out into that chocolate-dipped surf.

Kerosene-drum heart.

Curdling in a wet purgatory thousands of miles

from home. Imagine your grief inverted.

Your grandmother’s porcelain legs

with no sign of shatter.

Stitch them back together

with the black thread of your hair.

You’ll try, won’t you?

To recreate that teacup elegance.

What’s a holiday you can’t savor?

You, sourpuss.

You, spooky and spooked.

Pretend to be weightless.

No gravity.

No legs.

Just the velvety surf.

inviting you to forget.

Autumn Requiem

Our final October is the alarm clock’s keen.

You, with your proud surgeon’s hands, spin a trip as solution.

You contort the spine of our Metro-North tickets,

disguise errant jewels of conversation

as balm: mulled cider, an unimportant NPR podcast, my father’s birthday.

Those hard-earned pebbles of connectivity.

See, we still belong to one another.

The stiff wind at Storm King bites our cheeks red.

I love you like an earthquake loves its faults.

We trudge to Louise Bourgeois’ Eyes and pose for pictures.

We’re from the city, I say, by way of apology.

Maple leaves litter the ground: scarlett, orange, yellow.

I envy nature its luscious unburdening:

an annual, expected implosion.

My pupils inhale the map of your form, counting the years

I have charted. We, overgrown. It’s inevitable:

a scalpel dividing the inventory of our lives.

The erasure of shared language; the blurry concert tickets,

the bone-white tube of Crest no longer serving two.

You still have my copy of Kitchen Confidential,

nestled in the wooden crib of your bedside table.

I’ll buy you a Santoku knife in Tokyo, you’d promise.

You meant it then. In a past life, who were we to one another?

You, a mushroom of salt, dreaming in the Dead Sea.

I, the water, painting your crystals with my tongue:

erosion veiled as affection. Nothing survives here,

but oh, it was beautiful. How we’ve morphed now:

just two boxers, sheathed in metal,

circling the ring: each beginning to mourn

the other’s shadow.

Bio: Hailing from Virginia, Insiya Taj is a South-Asian American poet and healthtech professional. For the last decade, New York City has been her home. In August 2024, she was a featured poet for the “Embracing Every Hue” reading series curated by Darius Phelps. She is the winner of Brooklyn Poets’ 2024 Yawp Poem of the Year Contest.

Naqba

Part I –

June 2018: Palestinians protested at the border for the 70th anniversary of the Naqba (catastrophe) which signified when Israel forced hundreds of Palestinians from their homes. These protests went on for months. Layla was number 59

We are trapped inside *** an open air prison.

***** The only safe place / is within the womb /

Inside the womb, a fire burns, knowing what it once carried,

*********************************************************************** has left the earth.

Oh mamma of martyrdom/17 year old/not quite girl/but barely woman,

whose second born Layla, is named ‘beauty of the night.’

You ask, is it too much? for your second to be laid next to your first, who burned to

death, from a small flame, that lit the dark room

******************There has been no illumination in your eyes,

since the souls that you held inward, have continued,

********without your reach.

Even when we light a candle, it s W a l l o W s someone.

Even when the baby cries

for its’ mother,

or in search of her, it g a s p s soon after.

There is no wrinkle of remorse

from those who turned off the lights,

from those who aimed

at the smallest human.

All that she did was protest

*** silently, *** rightfully, *** peacefully

for their freedom. *** For our truth *** that we have hide

behind, *** but do not walk ***** in ***** front ***** of.

We are no martyrs, just watchers.

The daughter of the night

was not born for battle,

just born within the battlefield.

Layla, eight months old,

one hundred sixty nine days***** 1 6 9

in a war zone.

*** Eyes cracked O p e N ********** as she searched for her mother ********** one last time;

Only to return back

to the One that created her, and her mother’s soul.

She awaits His Gardens,

where she will meet her brother.

and he will touch ********** her tender face ********** for the first time.

Part II –

Brown women can’t leave,

can’t go back,

Back like black;

when black women

couldn’t have babies;

Couldn’t have babies

like unarticulated birth control

masked as immunization.

No black babies,

always an enigma.

Black woman

can’t have baby;

Baby stays with God;

God then welcomes back

brown baby;

Brown baby

that died alive;

Alive are the mothers’ screams;

Alive is the non-violent protest;

Alive are those in cages.

Cages contain our people;

People were once our babies,

Caged are the babies;

Babies die before

they enter the womb;

Babies die after

they exit the womb;

The womb is

the only safe prison;

The only prison

that has mercy.

Womb in Arabic is rehm,

rehm derived from

its’ root RA HA MA;

Ra ha ma then

becomes rehma;

rehma means mercy;

Maybe mercy is taking

the life of a baby,

so they don’t

have to go from

prison to cage;

Maybe mercy

is not letting

black babies

exist in the womb

in the rehm.

Because outside

the rehm – everyday

they will die —

a slow death.

Death is the

brown baby

on the news;

Death is the

final cry of

their mothers;

Death is living

in the realm

without feeling;

Maybe death,

death is life.

***

Fariha Tayyab is a multidisciplinary artist hailing from Houston. As a writer and photographer, her work revolves around the themes of identity and social justice. Fariha’s poetry and creative nonfiction are published in a variety of journals and publications. She has facilitated workshops with many programs, including the University of Iowa’s International Writing Program. Fariha has received awards and grants for her artistry, mentored emerging artists, and built community through local organizations.

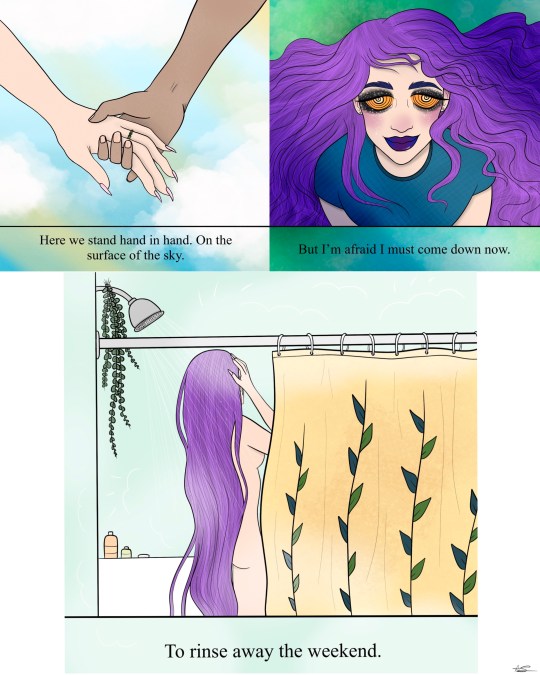

Rinse Away

*

Audrey Spuzzillo (she/her) is an illustration artist and recent graduate from The Cleveland Institute of Art (2023) with a passion for writing about women’s rights, ethereal and celestial subjects, as well as the personification of nature. Audrey utilizes her illustrations to further refine her poems to the next level of visual storytelling. Her illustrations mimic her poetic voice, often depicting spiritual concepts and whimsically romantic compositions to get lost in.

from “Twenty Collars”

15.

Life itself signed

The pock-faced earl

Sitting and looking down and straining over the atlas

As diapers climbed out a cloud, and dubbing over his chains,

“I understand ALL TOO WELL what you mean! Understanding while on

foot kills me instantly.

And that has dangled in its dullness for so long

we need the threat of violence to sense our attachment. But this value was

never dull.

As diapers climbed out of a cloud.”

16.

A treble clef entered the vault with a baby hung from the teat

A hand of circus fire was making sexy flamingos in the air ==

“all this—she lowed—where hair would be”

For it is a friend like me who ever haunts me and at the surface feeds me

the poison of everything I am to see otherwise—

*

Farnoosh Fathi is the author of Great Guns (Canarium Books) and the forthcoming Granny Cloud (NYRB Poets) , editor of Joan Murray: Drafts, Fragments, and Poems (NYRB Poets) and founder of the Young Artists Language and Devotion Alliance (YALDA). She lives in New York.

Analog

Words for the various levels of hell.

Words for the forest, the trails worn against it.

To name such places was to name limbo,

the way shot through with longing and starlight.

Each journey begins with loss

though when young we were taught to call it setting.

Then, to list it with other devices.

To touch it and put it down when we’re done.

On the floor, a mess of needles and soil.

Under the moss, rocks and water.

In the corners our forms moved

against each other, if movement was right

for the chosen word.

It’s important to write the ending first.

Not that you met someone else

but that frost is an alternate ending for night.

They called it the end but this was a circle.

Wasn’t the beginning a forest?

Wasn’t it dark?

In the underbrush branches shuddered.

Birds called how they do

when animals move through the distance below them.

*

Michael Goodfellow is the author of the poetry collections Naturalism, An Annotated Bibliography (2022) and Folklore of Lunenburg County (2024), both published by Gaspereau Press. His poems have appeared in the Literary Review of Canada, The Dalhousie Review, The Cortland Review, Reliquiae and elsewhere. He lives in Nova Scotia.

Synthetic Girl

Some edible heiress, lapsing as hot

wax, her lavender bones

spooning with glacial, inconsiderate drape:

encased, transparent, opaque, and primmed.

Yet the I slithers inside the skeletal drift,

imagining fresh, glowing aspirations

like the pricking wound of embarrassment:

ah, beauty dissimilar, slinky in dissent,

a revoked invitation. She is far and unfair,

a petulance enviable for its mobbish acquiescence.

Ghost, Euridice, what of his singing rocks

assembling the staircase to the basement?

I’ve heard of them, but did you?

*

Annie Goold is from a small farm in rural Illinois. She graduated from Cornell University in 2017 with an MFA in poetry. She is currently pursuing an MS in Clinical Mental Health Counseling at Eastern Illinois University. She lives and writes in Champaign, Illinois.

Uterus Revolt

“[Women] already make all the people […] You make all the humans. That’s a big fucking deal.”

Joe Rogan, Strange Times Netflix Special

Year one would be mostly medical:

midwives, doctors, hospitals, NICUs.

The diaper industry would take a hit.

All uteruses in quiet agreement.

The second fallout: downsizing daycare.

The silent shockwave of kindergarten.

1.5 million kindergarten teachers in the US

set up to enjoy a solid extended vacation.

Let’s set the record straight:

there is no miracle rib.

Babies grow in utero

and burst out of vaginas.

What happens when the government can no longer

procure babies from female bodies?

An IRB would frown upon growing

Homo sapiens in petri dishes.

Historically, power belongs to the oppressor.

Religion: a primer in female suppression.

Maybe, like Mary, we should all aspire

to parthenogenesis. Virgin birth.

No earthly penis is worthy of uterine holiness.

The sacrosanct womb holds no place for patriarchy.

*

Angel James is an easily distracted creative person from a sleepy, rural river town in Central Pennsylvania. She earned her Bachelor and Master of Arts degrees in English and a graduate certificate in Institutional Research and Assessment. Angel’s first book of poetry, Becoming Friends With Chaos, a collection of works inspired by the life and music of Bob Dylan, was released in 2022. You can learn more about her at angeljamescreates.com.